Have you ever given a colleague from another country some critical feedback and then been surprised by their reaction to it? Perhaps they even asked you for your opinion and then seemed taken aback by what you had to say.

The reason could be the style in which you gave your negative feedback. One size fits all definitely doesn’t apply to feedback.

Imagine the following situations:

- A colleague asks for your opinion on a report before he submits it. You notice some serious factual errors.

- While listening to a colleague’s presentation you notice that she does a couple of things that make it less effective than it could be.

Before you carry on reading, take a moment to think about how you would go about telling your colleague what you’ve noticed.

Straight to the point

Do you just tell it like it is? Do you get straight to the point with your negative feedback?

“The figures in Table 2 are completely out of date.”

“You didn’t have eye contact with the audience for most of your presentation.”

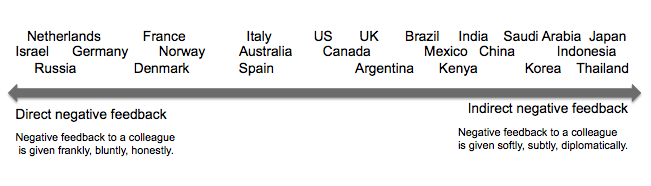

In countries including Russia, Israel, the Netherlands and – yes, you probably guessed – Germany negative feedback is often given in a very factual, direct fashion. The criticism stands alone without any positive comments. These four countries stand at the far end of the scale, but in France, Norway, Denmark, Italy, Spain and Australia, too, negative feedback is expressed pretty directly.

On the plus side: People who give feedback in this way certainly can’t be accused of beating about the bush or being insincere in any way. The message is delivered loudly and clearly. The focus is firmly on the behaviour that needs to be changed.

But recipients unused to this style will probably be taken by surprise. And because they are unprepared they may not be able to take in what is being said. A further risk is that the message can easily be understood as criticism of the person rather than the behaviour, leading to hurt feelings and damaging a previously good relationship.

Between the lines

At the other extreme are countries in which negative feedback is implicit, it is not directly mentioned at all. Merely hinted at between the lines or in what is left unsaid.

“(…) You are probably already intending to recheck the figures in Table 2, just to be on the safe side. (…)”

“I liked the way you established eye contact with the audience towards the end of the presentation.”

This style of feedback is used in many Asian countries, particularly in Japan, Thailand, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia and Korea and to a slightly lesser extent in India and China.

The great advantage here is that the recipient of the feedback does not lose face. Anyone attuned to this style can learn a lot without any embarrassment, without feeling that their weaknesses have been exposed.

But if you are unfamiliar with this approach you probably won’t receive the message at all and, especially if you asked your colleague for feedback, you’ll be frustrated that it isn’t forthcoming, that he or she doesn’t seem to be prepared to share their impressions with you.

Is a hamburger the answer to the problem?

So, is the solution to adopt the hamburger approach? Should you sandwich the critical message between praise and positive comments? Should you first make a positive comment (bottom half of the bun), then give the critical message (meat), and then top everything off with a further positive remark (top half of the bun)?

As I see it, the main advantage of this style is that it’s more balanced. There usually is something positive to be found in everyone’s behaviour. And it’s good to acknowledge this as well. In addition, as the conversation doesn’t just dive into the main point – the criticism – the recipient has time to prepare himself/herself for it.

But there are several serious problems with this approach. It may be difficult to pick out the real message. The meat may be buried between the two squashy halves of the bun – the criticism lost in between the two positive messages. There’s a risk of the other person remembering, and therefore focusing on, the first and last points they heard. The key point of the conversation may be forgotten.

However, the greatest disadvantage I see is that as the recipient becomes used to this approach to feedback, he/she probably won’t take the positive comments seriously, but see them as mere tactics. On the one hand this undermines trust – is this person’s positive feedback ever sincere or is it always just a tactic? On the other hand I believe it belittles the recipient. It assumes that he/she can’t deal with straight criticism, but needs it to be sugar-coated.

Bridging the gap

Instead I would suggest adapting your feedback style subtly to what is likely to be acceptable to the recipient and at the same time is authentic for you.

You can start by using the following information provided by Erin Meyer in her book The Culture Map to check what style of feedback the recipient is likely to be used to:

Assuming, for instance, that your country is much further to the left than that of the recipient, you could consider some of the following points to bridge the gap:

- You can give him or her a little time to prepare mentally by asking if it’s a good time.

- By avoiding upgraders (totally, absolutely, …) and/or using a few downgraders (a little, slightly, a bit) you can soften the blow.

- If you honestly liked an aspect of the report or presentation, why not praise it either before or after you give your criticism? This needn’t obscure your key message.

- And make absolutely sure that your criticism concentrates on the behaviour, not the person, and that the recipient cannot interpret it otherwise.

By the way, if you’re looking for useful phrases for giving negative feedback, you need look no further. 😉

*Different strokes for different folks is an expression meaning that different people approach things in different ways.